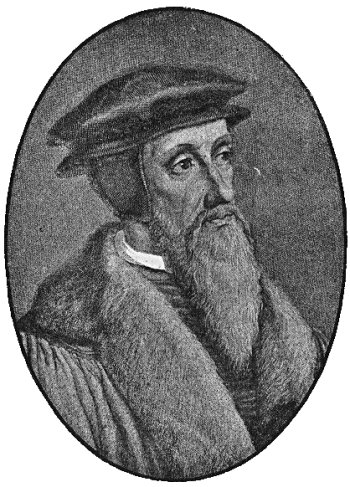

»Now no one doubts, that humility lies at the bottom of all true religion, and is the mother of all virtues. But how shall he be humble, who will not hear of the original sin and misery from which he has been delivered? and who, by extending the saving mercy of God to all, without difference, lessens, as much as in him lies, the glory of that mercy? Those, most certainly, are the farthest from glorifying the grace of God, according to its greatness, who declare, that it is, indeed, common to all men; but that it rests effectually in them, because they have embraced it by faith.

The cause of faith itself, however, they would keep buried, all the time, out of sight; which is this;—that the children of God, who are chosen to be sons, are afterwards blessed with the spirit of adoption. Now, what kind of gratitude is that, in me, if, being endowed with so pre-eminent a benefit, I consider myself no greater a debtor than he, who hath not received one-hundredth part of it. Wherefore, if, to praise the goodness of God worthily, it is necessary to bear in mind, how much we are indebted to Him; those are malignant towards Him, and rob Him of his glory, who reject, and will not endure, the doctrine of eternal election: which being buried out of sight, one-half of the grace of God must, of necessity, vanish with it.

Let those roar at us who will. We will ever brighten forth, with all our power of language, the doctrine which we hold concerning the free election of God; seeing that it is only by it, that the faithful can understand how great that goodness of God is, which effectually called them to salvation. I merely give the great doctrine of election a slight touch here, lest any one, by avoiding a subject so necessary for him to know, should afterwards feel what loss his neglect has caused him. I will, by and by, in its proper place, enter into the divine matter with appropriate fulness. Now if we are not really ashamed of the Gospel, we must, of necessity, acknowledge, what is therein openly declared;—that God, by his eternal good-will (for which there was no other cause than his own purpose), appointed those whom He pleased unto salvation, rejecting all the rest; and that those whom He blessed with this free adoption to be his sons, He illumines by his Holy Spirit, that they may receive the life which is offered to them in Christ; while others, continuing, of their own will, in unbelief, are left destitute of the light of faith, in total darkness.

Against this unsearchable judgment of God many insolent dogs rise up and bark. Some of them, indeed, hesitate not to attack God openly: asking why, foreseeing the fall of Adam, He did not better order the affairs of men? To curb such spirits as these, no better means need be sought than those which Paul sets before us. He supposes this question to be put by an ungodly person:—How can God be just, in showing mercy to whom He will, and hardening whom He will? Such audacity in men the apostle considers unworthy a reply. He does nothing but remind them of their order and position in God’s creation. “Who art thou, O man, that repliest against God?” (Rom. 9:20.) Profane men, indeed, vainly babble, that the apostle covered the absurdity of the matter with silence, for want of an answer. But the case is far otherwise.

The apostle, in this appeal, adopts an axiom, or universal acknowledgment: which not only ought to be held fast by all godly minds, but deeply engraven in the breast of common sense:—that the inscrutable judgment of God is deeper than can be penetrated by man. And what man, I pray you, would not be ashamed to compress all the causes of the works of God within the confined measure of his individual intellect? Yet, on this hinge turns the whole question.—Is there no justice of God, but that which is conceived of by us? Now if we should throw this into the form of one question,—whether it be lawful to measure the power of God by our natural sense,—there is not a man who would not immediately reply, that all the senses of all men combined in one individual must faint under an attempt to comprehend the immeasurable power of God: and yet, as soon as a reason cannot immediately be seen for certain works of God, men, somehow or other, are immediately prepared to appoint a day for entering into judgment with Him. What therefore can be more opportune or appropriate than the apostle’s appeal?—that those, who would thus raise themselves above the heavens in their reasonings, utterly forget who and what they are?«

Quelle: Calvin, John ; Cole, Hendry H.: Calvin’s Calvinism: A Treatise on the Eternal Predestination of God. London : Wertheim and Macintosh, 1856.