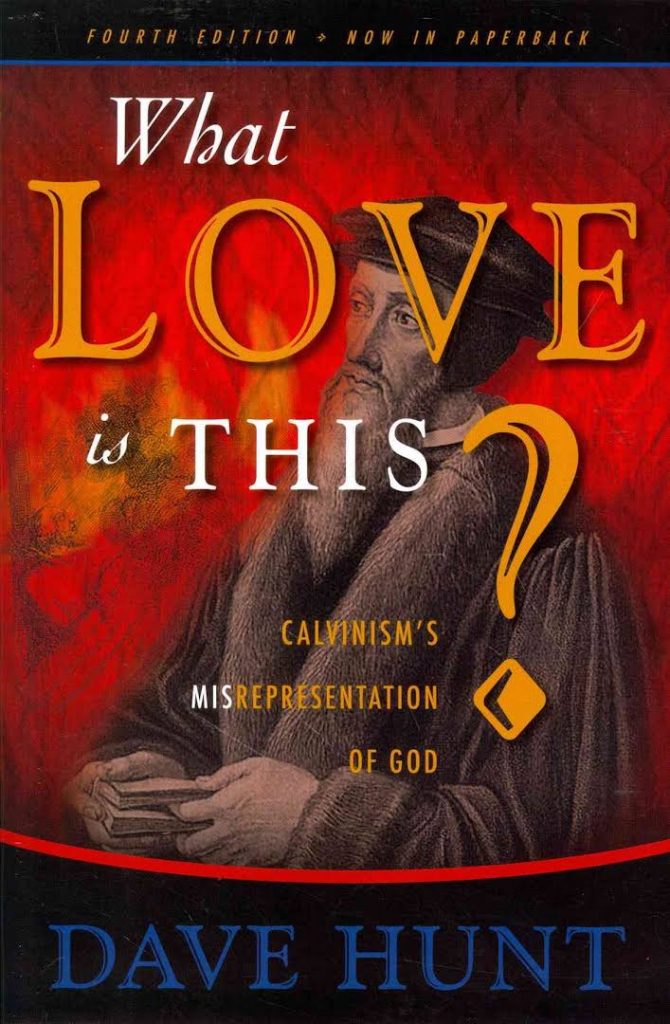

Diese Rezension des Originals des links abgebildeten, übersetzten Buches von Dave Hunt (1926–2013) stammt von Steven J. Cole. Dies ist eine adaptierte Übertragung dieser Rezension ins Deutsche.

Das Buch von Hunt wurde 2011 ins Deutsche übersetzt und von „Bible Baptist Ministries“ herausgegeben unter dem Titel: »Eine Frage der Liebe: Wird Gott im Calvinismus falsch dargestellt?« [Die Frage des Titels ist keine Frage, sondern Hauptthese des Buchs.] Cole schreibt:

»Als ich Dave Hunts neuestes Buch „What Love is This?“ mit dem Untertitel „Calvinism’s Misrepresentation of God“ [Titel der deutschen Ausgabe: „Eine Frage der Liebe: Wird Gott im Calvinismus falsch dargestellt?“] las, empfand ich sowohl tiefe Traurigkeit als auch gerechten Zorn. Ich war traurig, weil viele ahnungslose und ungebildete Christen glauben werden, dass Hunt Recht hat, und dadurch eine der reichsten geistlichen Goldminen verpassen, die es gibt, nämlich das Leben und die Schriften von Johannes Calvin und seinen Erben im Glauben. Ich war wütend, weil Hunt sowohl Calvin als auch den Calvinismus absichtlich falsch darstellt und verleumdet und dabei auch Gott selbst grob falsch darstellt. Ich weiß, dass seine Falschdarstellung Absicht ist, weil viele Calvinisten, darunter auch ich, während der Entstehung des Buches wiederholt an Hunt geschrieben haben, um ihn auf seine Fehler hinzuweisen und ihn zu bitten, mit der Falschdarstellung unseres Glaubens aufzuhören. Aber leider ignorierte er hartnäckig unsere Korrekturen und machte mit Volldampf weiter.

Das daraus resultierende Buch ist ein theologisches und geistliches Desaster ersten Ranges. Wenn Sie sich auf die Boulevardpresse als verlässliche Nachrichtenquelle verlassen, werden Sie wahrscheinlich feststellen, dass Hunt für Ihre Theologie zufriedenstellend ist. Er wird Ihnen dieselbe Art von sensationellen Verleumdungen liefern wie die Boulevardpresse, nur dass sie so präsentiert werden, als ob sie biblisch und historisch begründet wären. Aber wenn Sie in Ihrer Erkenntnis des lebendigen Gottes wachsen wollen, rate ich Ihnen, diese Boulevardtheologie ungelesen stehen zu lassen.

Ich musste mich mit dem Buch befassen, weil ein ehemaliger Ältester es an einige meiner Ältesten und andere weitergibt und ihnen sagt, es sei eine ausgewogene Kritik an der reformierten Theologie. Auf der Rückseite des Buches finden sich glühende Befürwortungen von Chuck Smith, Elmer Towns, Tim LaHaye und anderen. LaHaye sagt sogar: „Der Calvinismus … kommt der Blasphemie gefährlich nahe“ (Auslassungszeichen im Zitat). Mehrere Familien haben meine Kirche wegen dieser Frage verlassen, weil ich lehre, was die Heilige Schrift eindeutig bestätigt, nämlich dass Gott souverän beschließt, einige zu retten, aber nicht alle. Unsere Errettung beruht auf der Grundlage von Gottes souveräner Entscheidung für uns. Seine Entscheidung für uns ist der Grund dafür, dass wir uns für den Glauben entscheiden. Daher kann sich niemand seiner Errettung rühmen, sondern nur des Herrn (1. Korinther 1,26-31; Galater 1,15; Epheser 1,3-12).

Hunts Hauptkritikpunkt am Calvinismus ist dessen Ansicht, dass Gott nicht jedem Menschen gegenüber vollkommen liebevoll ist. Er argumentiert, dass Gott unmoralisch und ungerecht sei, wenn er alle Menschen retten könnte, sich aber dafür entscheidet, nur einige zu retten. So wie jemand, der einen Ertrinkenden retten könnte, es aber nicht tut, unmoralisch wäre (S. 111–112, 114–115). Hunt vertritt die Ansicht, dass Gott möchte, dass alle Menschen gerettet werden, und dass er allen die Rettung ermöglicht habe. Nun liegt es am Einzelnen, darauf zu reagieren, und jeder Mensch sei aus sich selbst in der Lage, darauf zu reagieren. Wenn die Menschen nicht in der Lage wären, aus freiem Willen auf das Evangelium zu antworten, dann wäre das Heilsangebot Gottes nicht echt, sondern eine Verhöhnung. Es wäre so, als ob Gott einem Menschen, der in einem tiefen Brunnen gefangen ist, ein Seil außerhalb dessen Reichweite hielte und sagte: „Nimm das Seil.“ Das sind die Argumente von Hunt.

Diese Argumente entsprechen durchaus der menschlichen Denkweise, aber die entscheidende Frage ist, ob sie mit der biblischen Offenbarung übereinstimmen. Hunt geht fälschlicherweise davon aus, dass das freie Angebot des Evangeliums an alle voraussetze, dass diejenigen, denen es angeboten wird, auch in der Lage seien, darauf [heilsergreifend] zu antworten. Es gibt jedoch viele Bibelstellen, die direkt auf die Unfähigkeit des Sünders hinweisen, auf die geistliche Wahrheit [heilsergreifend] zu antworten (Johannes 6,44.65; 8,43; Römer 3,10–18; 8,6–8; 1. Korinther 2,14; 2. Korinther 4,4; Epheser 2,1–3 usw.). Hunt verwirft oder verwässert all diese Texte, indem er sagt, dass sie nicht das bedeuten könnten, was die Calvinisten behaupten, denn wenn sie das bedeuten würden, könnten die Sünder nicht auf das Evangelium reagieren und somit wäre das Angebot des Evangeliums nicht gültig. Mit anderen Worten, er argumentiert im Kreis und nimmt an, was er später „beweist“. Aber er akzeptiert nicht die klare Lehre von Gottes Wort, dass der Mensch wegen des Sündenfalls unfähig ist, nach Gott zu suchen. Damit zieht Hunt Gott in seiner absoluten Heiligkeit herab auf das Niveau des gefallenen Menschen und macht ihn so für den gefallenen Menschen greifbar. Gleichzeitig erhebt er den sündigen, stolzen Menschen, indem er ihm behauptet, er könne sich jederzeit für Gott entscheiden.

Nach der Verwerfung der biblischen Lehre der Verderbtheit (Unfähigkeit) des gefallenen Menschen, fährt er fort, auch alle anderen der so genannten Fünf Punkte des Calvinismus zu verwerfen. Hunt behauptet, dass Gott unmöglich einige Menschen souverän zum Heil erwählt haben könne, denn dann wäre er lieblos und ungerecht. Dabei ist es ihm offenbar völlig egal, dass Gott in einer seiner frühesten Selbstoffenbarungen klar und deutlich sagt: »[I]ch werde begnadigen, wen ich begnadigen werde, und werde mich erbarmen, wessen ich mich erbarmen werde« (2. Mose 33,19). Diese Aussage verliert jeden Sinn, wenn Gott jedem einzelnen Menschen gegenüber gleichermaßen gnädig und barmherzig ist. Von Anfang an begründet Gott sein Recht als heiliger Gott, einige auszuwählen und andere abzulehnen, nicht aufgrund menschlicher Verdienste (die es nicht gibt), sondern aufgrund seines souveränen Willens. Doch Hunt spricht Gott dieses Vorrecht ab, obwohl die Heilige Schrift dieses überaus häugfig offenbart.

Während er seine humanistische (und unbiblische) Sicht von Gott darlegt und verteidigt, zerreißt Hunt Calvin und den Calvinismus – oder zumindest glaubt er, dass er das tut. In Wirklichkeit versteht Hunt nicht einmal einige der grundlegenden Lehren des Calvinismus, obwohl er glaubt, dass er sie versteht. So stellt Hunt von Anfang an und auf praktisch jeder Seite falsch dar, was Calvinisten glauben. Auch wenn er nicht mit dem übereinstimmt, was sie wirklich glauben, so stellt er doch größtenteils eine Karikatur auf und greift sie an, die manchmal eine gewisse Ähnlichkeit mit der Wirklichkeit hat, aber meistens so weit davon entfernt ist, dass biblisch informierte Calvinisten sie ebenfalls angreifen würden. Sie würden es nur nicht als Calvinismus bezeichnen, wie Hunt es fälschlicherweise tut. Hier sind ein paar (von vielen) Beispielen:

- Hunt sagt, dass der Calvinismus die rettende Gnade Gottes auf einige wenige Auserwählte beschränke und die Mehrheit der Menschheit ohne Hoffnung oder Möglichkeit auf Erlösung lasse (S. 78). Das Angebot der Errettung gelte nur den Auserwählten (S. 103). In Wahrheit glauben Calvinisten, dass Gottes rettende Gnade der ganzen Welt frei angeboten wird und dass es im Himmel eine unzählige Schar aus allen Stämmen der Erde geben wird, die durch das Blut Jesu erkauft wurde (Offenbarung 5,9–12).

- Hunt sagt, dass der Calvinismus die Schuld für die Sünde und die Verdammnis der Sünder vollständig Gott zuschreibe, der alles so vorherbestimmt habe, dass es so kommen musste (S. 84). Gott veranlasse alle Menschen zur Sünde (S. 42). Die Wahrheit ist, dass Calvinisten glauben, dass zwar alles unter Gottes souveränem Willen steht (Epheser 1,11), er aber nicht der Urheber der Sünde ist. Die Sünder sind für ihre eigene Verdammnis verantwortlich, und niemand kann Gott dafür verantwortlich machen, dass sie in die Hölle kommen. Ich habe Hunt persönlich auf das Westminster Glaubensbekenntnis, Kapitel 3, Absatz 1, verwiesen, in dem die reformierte Erklärung steht, dass Gott souverän über alles ist und dennoch nicht für die Sünde verantwortlich ist. Aber Hunt hat dies ignoriert und bleibt bei seiner verleumderischen Anschuldigung.

- Hunt sagt, der Calvinismus leugne jede echte Wahlmöglichkeit des Menschen (S. 89). In Verbindung damit leugneten die Calvinisten, dass der Mensch einen Willen habe (S. 94). „Calvin zufolge hat die Erlösung nichts damit zu tun, ob ein Mensch an das Evangelium glaubt oder nicht“ (S. 42). Die Wahrheit ist, dass Calvin und die Calvinisten an die menschliche Wahl und den Willen glauben. Sie behaupten jedoch, dass der gefallene Mensch, wie sogar der Arminianer Wesley es ausdrückte, „fest in der Sünde und der Nacht der Natur gefangen“ sei, unfähig, sich für das Heil zu entscheiden, wenn nicht Gott souverän in ihren Herzen wirkt. Ich bin mir nicht sicher, woher Hunt die lächerliche Behauptung hat, Calvin habe die Erlösung vom Glauben getrennt. Eine einfache Lektüre seiner Kapitel über Glauben und Umkehr in der Institutio (Buch 3, Kapitel 2 und 3) zeigt, dass Hunt Calvin entweder nicht gelesen hat oder ihn absichtlich falsch darstellt.

- Hunt sagt: „Der Calvinismus präsentiert einen Gott, der die Hölle mit denen füllt, die er retten könnte, aber stattdessen verdammt, weil er sie nicht liebt“ (S. 116). Hunt behauptet dreist, dass Gott, wenn er nicht allen Barmherzigkeit erweist, obwohl alle gleich schuldig sind, die Gerechtigkeit pervertiere (S. 115)! Die Wahrheit ist, dass Calvinisten behaupten, Gott sei mächtig, alle zu retten, die er retten will (z. B. den Apostel Paulus). Aber er ist niemandem das Heil schuldig. Aus Gründen, die nur im geheimen Ratschluss seines Willens bekannt sind, hat Gott beschlossen, sowohl in der Errettung seiner Auserwählten als auch in der gerechten Verdammnis derer, die gegen ihn rebelliert haben, verherrlicht zu werden. Das gesamte Argument des Paulus in Römer 9 lautet, dass Gott als göttlicher Töpfer das Vorrecht hat, einige Gefäße für die Barmherzigkeit und andere für den Zorn zu machen, und dass wir keinen Grund haben, sein Handeln in Frage zu stellen. Die Bibel macht auch deutlich, dass Gottes Liebe nicht allen Menschen in gleicher Weisezuteil wird. Er liebte Israel, aber er beschloss nicht, die umliegenden Völker in gleichem Maße zu lieben (5. Mose 7,6–8). In seinem unergründlichen Willen ließ er es zu, dass die Völker viele Jahrhunderte lang ihren eigenen Weg in der geistlichen Finsternis gingen. Er gab ihnen das Zeugnis seiner Güte durch die Schöpfung und die allgemeine Gnade, was ausreicht, um sie zu verdammen, aber nicht, um sie zu retten (Apostelgeschichte 14,16–17; Römer 1,18–32). Seltsamerweise argumentiert Hunt jedoch entgegen der Schrift und der Geschichte, dass Gott alle Heiden genauso liebe wie seine auserwählte Braut, die Kirche. Ich möchte von ihm wissen, wie Gott die amerikanischen Indianer, die hier [in Nordamerika] vor 3.000 Jahren lebten, in gleichem Maße geliebt hat, wie er König David liebte und sich ihm offenbarte? Ein kurzer Blick auf die heutige Welt zeigt, dass nicht alle die gleiche „Chance“ haben, das Evangelium zu hören und darauf zu reagieren.

Um den Calvinismus zu diskreditieren, muss Hunt Calvin und seine berühmte Institutio diskreditieren. Man mag es kaum glauben, aber Hunt verwirft die gesamte Institutio in einem Pauschalurteil, indem er behauptet, sie stammte aus den beiden Hauptquellen Augustinus und der lateinischen Vulgata-Bibel (S. 38)! Da Calvin ein Neubekehrter war, als er die erste Ausgabe der Institutio schrieb, könne sie „unmöglich aus einem tiefen und voll entwickelten evangelischen Verständnis der Schrift stammen“. Aber Hunt erwähnt nicht, ob sie tatsächlich ein solches Verständnis widerspiegeln oder nicht! Wenn sie so oberflächlich waren, wie Hunt behauptet, warum hatten sie dann einen so tiefgreifenden Einfluss, nicht nur auf seine Generation, sondern auch auf gottesfürchtige christliche Gelehrte durch die Jahrhunderte hindurch, bis in die heutige Zeit? Ich kann persönlich bezeugen, dass von den Hunderten von Büchern [außerhalb der Bibel], die ich je gelesen habe, keines der Institutio in Bezug auf ihre tiefe geistliche Erkenntnis das Wasser reichen kann. Calvin nutzt die Heilige Schrift, um Gott zu erheben und zu preisen und mich als Sünder zu demütigen, wie es nur wenige Autoren vermögen.

Was den Menschen Calvin betrifft, so behauptet Hunt, dass dieser so stark von Augustinus beeinflusst war, dass er sich nie wirklich von seinen römisch-katholischen Wurzeln gelöst habe. Er lehnt Augustins Schriften völlig ab, indem er behauptet: „Calvin schöpfte aus einem stark verschmutzten Strom, als er die Lehren des Augustinus annahm! Wie könnte man in eine so verunreinigende Ketzerei eintauchen, ohne verwirrt und infiziert zu werden?“ (S. 51). Ich muss mich fragen, ob Hunt Augustinus überhaupt gelesen hat! Ich habe große Teile der Werke von Augustinus gelesen, und obwohl er offensichtlich an einigen Stellen von der katholischen Kirche auf schlimme Weise verdorben wurde, hatte er auch ein solides biblisches Verständnis vieler wesentlicher christlicher Lehren. Ihn als „stark verunreinigten Strom“ und als Verfechter einer „verunreinigenden Ketzerei“ abzutun, zeugt von Hunts, nicht von Augustins Unwissenheit und Irrtum.

Auch wenn Calvin Augustinus oft positiv zitiert (weil es viel Positives zu zitieren gibt und weil Calvin nicht annähernd über die theologischen Ressourcen verfügte, auf die wir zurückgreifen können), streitet er oft mit Augustinus, wenn er meint, dass dieser die Schrift nicht richtig ausgelegt hat. Calvins einzige Quelle der Wahrheit war die Bibel, wie T. H. L. Parkers ausgezeichnetes Buch Calvin’s Preaching [Westminster/John Know Press] so gekonnt aufzeigt. Hätte Hunt entweder Augustinus oder Calvin sorgfältig gelesen, hätte er gesehen, dass diese Männer versuchten, ihre Lehren allein auf die Bibel zu stützen. Natürlich haben beide Männer Fehler gemacht. Wer tut das nicht? Aber wenn man diese Männer liest, spürt man: „Sie kannten Gott auf eine Weise, wie ich Gott nicht kenne!“

Hunt stellt Calvin als den bösen Tyrannen von Genf dar, der versuchte, dem Volk die unwiderstehliche Gnade aufzuzwingen, ganz im Einklang mit seiner Auffassung, dem Menschen jegliche Entscheidungsfreiheit abzusprechen (S. 62–63). „Calvin übte eine ähnliche Autorität aus wie das Papsttum, das er nun verachtete“ (S. 63). Hunt wirft Calvin vor, eine „diktatorische Kontrolle über die Bevölkerung“ auszuüben (S. 64). Er habe die Anwendung von Folter zur Erlangung von Geständnissen gebilligt, einschließlich der grausamen 30-tägigen Folterung eines Opfers, das dann an einen Pfahl gebunden, mit den Füßen festgenagelt und enthauptet wurde (S. 65). Und natürlich macht Hunt Calvin für die Verbrennung von Servetus verantwortlich, ohne seinen Lesern den historischen Kontext zu erläutern (S. 68–70). Hunt kommt zu dem Schluss, dass „Calvins Verhalten Tag für Tag und Jahr für Jahr das genaue Gegenteil dessen war, was er getan hätte, wenn er wirklich vom Geist Gottes geleitet worden wäre“ (S. 72). Mit all diesen Anschuldigungen knüpft Hunt an militante antichristliche Kritiker wie Voltaire, Will Durant, Erich Fromm und andere an (siehe Christian History[Bd. V, Nr. 4], S. 3).

Natürlich hatte Calvin Feinde, sogar zu seiner Zeit, die seine Schwächen aufgriffen und sie übertrieben, um ihn zu verleumden, weil ihnen seine Lehre nicht gefiel. Jeder gottesfürchtige Mensch muss damit rechnen, dass er auf die eine oder andere Weise so behandelt wird (Matthäus 5,11–12; Lukas 6,26; 2. Timotheus 3,12). Aber jeder, der T. H. L. Parkers Das Leben Calvins, sein Die Predigten Calvins oder Bezas Das Leben Calvins (Beza war Calvins Schüler und Nachfolger in Genf) gelesen hat, wird entsetzt sein, wie ein bekennender Christ einen großen Mann Gottes wie Calvin so rücksichtslos angreifen kann, wie Hunt es tut. Über Calvin sagte Beza: „Ich war sechzehn Jahre lang sein Zeuge, und ich glaube, dass ich das volle Recht habe zu sagen, dass in diesem Mann allen ein Vorbild für das Leben und Sterben eines Christen gezeigt wurde. Es wird nicht leicht sein, es herabzusetzen, und es wird schwer sein, es nachzuahmen“ (Christliche Geschichte, ebd., S. 2).

Die schlichte Tatsache der Geschichte ist, dass die gottesfürchtigen Puritaner, einschließlich John Bunyan und John Owen, sowie die geistlichen Giganten Jonathan Edwards, George Whitefield, Charles Simeon, Charles Spurgeon, die Princeton-Theologen, Martyn Lloyd-Jones, Francis Schaeffer und eine Vielzahl anderer auf Calvin nicht nur als klugen Theologen, sondern auch als großes Vorbild der Frömmigkeit geschaut haben. Ich habe die Institutio gelesen, etwa ein halbes Dutzend Calvin-Biografien, Tausende von Seiten seiner Kommentare, zahlreiche Bücher über Calvin und seine Theologie sowie mehrere Bücher mit seinen Predigten. Ich habe nie etwas aufgeschnappt, das auch nur annähernd der Karikatur von Hunt über diesen Mann entspricht. Ich stimme dem gelehrten schottischen Theologen William Cunningham zu, der sagte: „Calvin ist der Mann, der neben dem heiligen Paulus am meisten Gutes für die Menschheit getan hat“ (Christian History, ebd.). Der Angriff von Hunt ist einfach unter aller Kritik. Ein böser, grausamer Tyrann hätte keine so erhabenen Ansichten über Gott und so tiefe Einblicke in Gottes Wort schreiben können, wie sie in Calvins Schriften zu finden sind. Wenn so viele große Männer Gottes Calvin Tribut zollen, sollte Hunt dann nicht wenigstens in Betracht ziehen, dass er etwas übersehen haben könnte?

Ein weiteres großes Problem der Arbeit Hunts ist seine unwissenschaftliche Manipulation des Quellenmaterials, damit es seinen Zwecken diene. Für seine Angriffe auf Calvin zitiert er oft den militanten Gegner des Christentums Will Durant, ohne jemals zuzugeben, dass er einen Feind des Glaubens zitiert. Er zitiert oft den liberalen Frederic Farrar, ohne dessen theologische Voreingenommenheit zuzugeben. Obwohl Hunt in seinen anderen Schriften militant antikatholisch ist, beruft er sich auf den prokatholischen Führer der Oxford-Bewegung, Pusey, wenn dieser sich auf die Seite von Hunt gegen den Calvinismus stellt. Aber Hunt erwähnt nicht einmal in einer Fußnote die theologische Voreingenommenheit seiner Quellen. Unwissende Leser könnten meinen, dass er große Männer des Glaubens zitiert.

Aber viel schlimmer ist die Art und Weise, wie er Quellen benutzt, um eklatante historische Fehler zu „beweisen“! Er zitiert eine Quelle (S. 19), die behauptet, dass unter anderem Richard Baxter, John Newton und John Bunyan gegen den Calvinismus waren! Jeder, der diese Männer gelesen hat, weiß, dass sie alle starke Befürworter der souveränen Erwählung durch Gott waren. (Baxter vertrat ein universales Sühnopfer, aber er war auch ein starker Befürworter der menschlichen Verderbtheit und der souveränen Erwählung durch Gott.) Auf derselben Buchseite zieht er ein Zitat aus Spurgeons Autobiographie heran, um zu beweisen, dass Spurgeon gegen das begrenzte Sühnopfer war. Aber im ursprünglichen Kontext argumentierte Spurgeon für die begrenzte Versöhnung (Autobiographie von C. H. Spurgeon [Banner of Truth], 1:171–172)! Tatsächlich stellt Spurgeon fest (1:172), dass die Lehre, Christus sei für alle gestorben, „tausendmal abstoßender ist als irgendeine der Folgen, die man mit der calvinistischen und christlichen Lehre von der besonderen und partikulären Erlösung in Verbindung bringt.“ Später (S. 122) zitiert Hunt „einen britischen Gelehrten, der Spurgeons Schriften und Predigten gründlich kannte“, um erneut festzustellen, dass Spurgeon das begrenzte Sühnopfer definitiv ablehne und dem Menschen Willensfreiheit zuspreche. In seinem Literaturverzeichnis (S. 428) führt Hunt jedoch Spurgeons Predigt „Free-Will – A Slave“ auf, in der Spurgeon den freien Willen widerlegt [2. Dezember 1855, Text: Johannes 5,40; New Park Street Pulpit, Bd. 1]. Iain Murray (The Forgotten Spurgeon [Banner of Truth], S. 81 ff.) führt zahlreiche Referenzen an, um zu zeigen, dass Spurgeon nicht nur die „begrenzte Sühne“ bejahte; er argumentierte auch, dass diejenigen, die sie leugnen, die gesamte Lehre der stellvertretenden Sühne schwächen und untergraben. In seiner Autobiographie (1:168) bezeichnete Spurgeon den Arminianismus (was Dave Hunts Ansicht ist, auch wenn Hunt dies leugnet, da er an der ewigen Sicherheit festhält) als Irrlehre und sagte klar und deutlich: „Der Calvinismus ist das Evangelium und nichts anderes.“ Entweder ist Hunt ein sehr schlampiger Gelehrter, oder er versucht absichtlich, seinen Lesern vorzugaukeln, dass Spurgeon auf seiner Seite steht, obwohl er genau weiß, dass das nicht der Fall ist.

Auf Seite 102 zitiert Hunt erneut Spurgeon und behauptet, er „könne die Lehre nicht akzeptieren, dass die Wiedergeburt vor dem Glauben an Christus durch das Evangelium komme“. Offensichtlich zitiert er Spurgeon aus dem Zusammenhang gerissen für seine eigenen Zwecke (wie er es häufig tut), ohne irgendein Verständnis von Spurgeons Theologie zu haben. Murray (ebd., S. 90 ff.) dokumentiert ausführlich, dass Spurgeon glaubte, dass Glaube und Umkehr unmöglich sind, bevor Gott den Sünder neues Leben schenkt. Zum Beispiel zitiert Murray (S. 94) Spurgeon mit den Worten, dass Buße und Glaube „das erste offensichtliche Ergebnis der Wiedergeburt“ seien. Und: „Evangelische Reue kann niemals in einer nicht-wiedergeborenen Seele existieren.“ Murray führt viele weitere Beispiele an. Spurgeon glaubte, „dass das Werk der Wiedergeburt, der Bekehrung, der Heiligung und des Glaubens nicht ein Akt des freien Willens und der Kraft des Menschen ist, sondern der mächtigen, wirksamen und unwiderstehlichen Gnade Gottes“ (S. 104).

Auf Seite 100 findet sich ein weiteres Beispiel dafür, wie Hunt aus dem Zusammenhang gerissene Zitate verwendet, um seinen Gegner schlecht und sich selbst gut aussehen zu lassen. Er zitiert R. C. Sproul, um so zu klingen, als ob Sproul die Ansicht, dass Gott den Sündern gegenüber nicht so liebevoll ist, voll und ganz befürwortet. Aber im vorhergehenden und nachfolgenden Kontext von Sprouls Buch wirft Sproul einen Einwand auf, den ein Kritiker stellen könnte, räumt den Einwand des Kritikers um des Argumentes willen als wahr ein und wirft dann eine weitere Frage auf, um zu zeigen, dass die Frage des Kritikers fehlgeleitet ist. Hunt lässt den Kontext weg und lässt Sproul so erscheinen, als würde er etwas sagen, was er gar nicht sagt! Das ist wissenschaftlich und argumentativ unglaublich schlechtes Arbeiten von Hunt.

Auf Seite 99 offenbart Hunt seine Unkenntnis der Theologie, wenn er behauptet, dass J. I. Packer seinen calvinistischen Mitstreitern und sogar sich selbst widerspreche, wenn er erkläre, dass die Wiedergeburt dem Glauben und der Rechtfertigung folge. Hunt zitiert dann einen Satz von Packer, der von Rechtfertigung durch Glauben spricht, nicht von Wiedergeburt! Das sind unterschiedliche theologische Begriffe mit unterschiedlichen Bedeutungen, wie jeder, der auch nur ein rudimentäres Verständnis von Theologie hat, weiß! Aber egal, Hunt diskreditiert Packer gegenüber dem ahnungslosen Leser, und das ist alles, was für Hunt zählt.

Es wäre ein Leichtes, diese Rezension auf Buchlänge auszudehnen, denn die Irrtümer, die fehlerhafte Logik und die grobe Fehldarstellung des Calvinismus und des Gottes der Bibel nehmen einfach kein Ende. Sowohl in der persönlichen Korrespondenz mit Hunt vor der Veröffentlichung des Buches als auch bei der Lektüre des Buches selbst habe ich mich gefragt, wie es um Hunts persönliche Integrität bestellt ist. Wenn er wirklich nicht weiß, was Calvinisten glauben, hätte er das Buch nicht schreiben dürfen, bevor er nicht ein angemessenes Verständnis ihrer Ansichten gewonnen hat. Es ist nicht so, dass Hunt nicht vorher mit dieser Frage konfrontiert worden wäre. Außer mir haben ihn eine Reihe von Reformierten gewarnt, dass er den reformierten Glauben falsch darstelle. Aber er ignorierte diese Warnungen und stürmte weiter vor sich hin. In Kapitel 2 begründet er sein Vorgehen mit der Behauptung, dass Calvinisten elitär seien und dass der Calvinismus nicht biblisch sein könne, weil er so schwer zu verstehen sei, dass [auch] Hunt ihn nicht verstehen könne. Ich kenne jedoch viele, die jung im Glauben sind und diese Lehren sehr gut verstehen. Hunt hätte lange genug innehalten sollen, um die gegnerische Ansicht zu verstehen, damit er sie nicht falsch darstellt. Seine Angriffe auf sein selbstgebasteltes Feindbild diskreditieren ihn, er ist einfach kein seriöser Kritiker.

Obwohl Hunt energisch widersprechen würde, glaube ich, dass der Grund für seinen verleumderischen Angriff auf Calvin und die Calvinisten und seine blasphemischen Anschuldigungen gegen den Gott der Bibel in seiner Weigerung liegt, sich einer klaren biblischen Offenbarung zu fügen, die nicht in die menschliche Logik passt. Nachdem er erklärt hat, dass Gott sich erbarmt, wem er will, und verhärtet, wen er will, erhebt Paulus den Einwand: »Ihr werdet dann zu mir sagen: ‚Warum findet er noch Schuld? Denn wer widersetzt sich seinem Willen?’« (Römer 9,19). Die logische Antwort von Dave Hunt lautet: „Der Grund, warum Gott zu Recht Fehler finden kann, ist, dass er jedem Menschen einen freien Willen und die Möglichkeit zur Erlösung gegeben hat.“ Das ist logisch vollkommen einleuchtend. Aber das Problem ist, dass das nicht die biblische Antwort ist! Die biblische Antwort lautet: „Im Gegenteil, wer bist du, o Mensch, der du Gott vorwurfsvoll entgegentrittst? Das Geformte wird doch nicht zu dem, der es geformt hat, sagen: ‚Warum hast du mich so gemacht‘, oder?“ Mit anderen Worten, die Antwort Gottes lautet: „Du hast kein Recht, diese Frage zu stellen!“

Ich gebe zu, diese Antwort ist logisch nicht befriedigend! Vor Jahren, als ich Student war, habe ich mit Paulus darüber gestritten und ihm vorgeworfen, dass er sich genau dann aus dem Staub macht, wenn ich eine Antwort auf meine Frage brauche. Eines Tages, als ich mit Paulus stritt, öffnete mir der Herr die Augen und ich sah. Er sagte: „Ich habe die Frage beantwortet, weißt du! Du magst nur die Antwort nicht!“ Da wurde mir klar, dass ich mich dem unterwerfen musste, was Gott durch Paulus geschrieben hatte. An diesem Tag wurde ich zum „Calvinisten“, obwohl ich noch keine einzige Seite von Calvin gelesen hatte. Wenn Dave Hunt seine Logik der Offenbarung Gottes in der Heiligen Schrift unterwerfen würde, würde er auch das werden, was er jetzt hasst und so grob falsch darstellt: ein „Calvinist“! Verschwenden Sie Ihre Zeit nicht mit der Lektüre von Dave Hunt. Nehmen Sie sich ein Exemplar von Calvins Institutio und beginnen Sie, sich an der Majestät Gottes zu erfreuen!«

Fazit

Dieses Buch von Dave Hunt hat aufgrund der zahlreichen Strohmann-Attacken, des Beharrens von Hunt, nachgewiesene Fehler nicht einzugestehen und zu beseitigen sowie wegen seines verleumderischen Charakters einen Platz in der „Hall of Shame“ wohl verdient.

Über den Autor der Rezension

Steven J. Cole diente seit Mai 1992 der christlichen Gemeinde Flagstaff Christian Fellowship als Pastor bis zum Eintritt in den Ruhestand im Dezember 2018. Von 1977 bis 1992 war er Pastor der Lake Gregory Community Church in Crestline, Kalifornien. Er ist Absolvent des Dallas Theological Seminary (Th. M., 1976 in Bible Exposition) und der California State University in Long Beach (B. A., philosophy, 1968). Er hat Freude am Schreiben; seine Beiträge wurden in vielen unterschiedlichen Publikationen veröffentlicht. .

Textquelle

https://bible.org/article/what-theology-dave-hunt-s-misrepresentation-god-and-calvinism [03.JUN.2020]

Ergänzendes

Die große calvinistische Verschwörung. Eine Stellungnahme zu Vorwürfen von T. A. McMahon [03.JUN.2020]